VAMPIRES: A SCIENTIFIC REVIEW

ABSTRACT: Vampires are frequent creatures in horror stories. However, the myth originated as an explanation for the diseases and deaths that occurred in a period in which knowledge about death and the transmission of diseases was almost zero. Recent studies show that some of the diseases that could have contributed to the creation of the myth are plague, rabies, pellagra, tuberculosis, and porphyrias; whose symptoms resemble some characteristics associated with vampires such as blood consumption and photosensitivity.

Keywords: Vampire, myth, contagious disease, corpse decay.

INTRODUCTION

Vampires are commonly present in our popular culture, and their appearance can now be found in various formats such as literature, cinema, TV series, and even video games. The vampire figure as we know it has its origin in 19th-century literature. Some of its first appearances go back to 1872 and 1897 with the publications of Carmilla, by Sheridan Le Fanu, and Dracula, by Bram Stoker, respectively [1].

Hematophagous creatures have been widely mentioned since ancient folklore by the Mesopotamian cultures, the Romans, and the Greeks. Nevertheless, stories about bloodsuckers spread especially during medieval Europe in times of hysteria and disease. The lack of knowledge of death and infectious illness, mixed with fear, gave rise to the creation of myths and superstitions as a way to explain what was not understood [1, 2].

Research from the last two centuries proposes that the origin of vampires can be related to certain diseases [2] which, although they do not cause vampirism as such, may induce physical and psychological abnormalities that closely resemble characteristics associated with these legendary creatures [3].

Therefore, this writing aims to illustrate the roots of the vampire myth through science, exemplifying some of the diseases that could give it life.

ANALYSIS

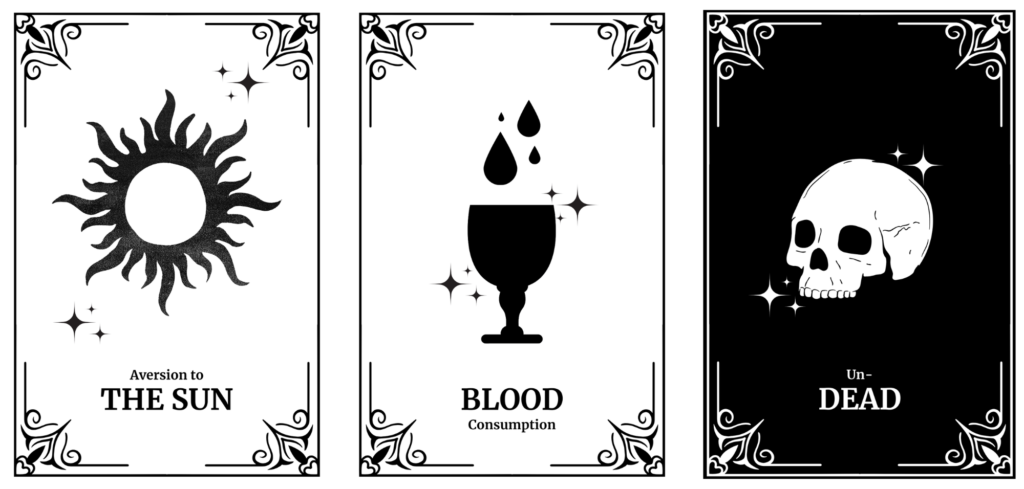

Before breaking down the myth, it seems necessary to mention the main features that characterize a vampire (Figure 1). Unfortunately, the figure of the vampire can not be condensed into a single definition, since its description varies within folklore. However, the most distinctive feature of the vampire myth is the consumption of blood or some type of “essence”. This trait is followed by the possession of fangs, the frequent description as “undead”, as well as pale skin and an appearance that is either unpleasant or very beautiful, depending on the story. Likewise, they are credited with the absence of shadow or reflection [2].

Now some of the diseases linked to the vampire myth, especially during the “vampire epidemic” in Eastern Europe, will be exposed.

Figure 1. Some characteristics associated with vampires.

1. The First Way to Turn into a Vampire: Plague.

Plague is a zoonotic, transmissible from animals to humans, bacterial disease that presents important mortality to small mammals. It is caused by Yersinia pestis, a Gram-negative bacillus in the family Enterobacteriaceae [4, 5].

There are three ways in which this disease can develop in humans: pneumonic, bubonic, and septicemic. Pneumonic plague is acquired when the bacteria enters the body through respiration, infecting the lungs. This is the most aggressive and deadly form of the plague and its incubation can be as short as 24 hours. Moreover, the bite of an infected flea transmits the bubonic plague and is the most common form of the disease. It is characterized by the formation of “buboes”, and painful swollen lymph nodes. Even if this form is less lethal than pneumonic plague, it still has a high mortality rate. Finally, septicemic plague is acquired the same way as bubonic plague but there is no development of the buboes. In this form, the bacteria multiply in the blood. This can be a complication of the other varieties of plague or just develop like this [4, 5, 6].

Throughout history, there have been several plague epidemics. However, the outbreaks in Eastern Europe between 1663 and 1772 concur with the “vampire epidemic” in 1730. Therefore, it’s possible that people who suffered or died from the plague were related to the figure of the vampire; especially if the pneumonic variant of the disease was present, since during the infection it is common to present bloody sputum from the cough and this could be associated with the consumption of blood, characteristic of a vampire [7].

2. The Second Way: Rabies.

Rabies is a zoonotic viral disease that attacks the central nervous system. The rabies virus has a distinctive “bullet” shape and is classified in the Rhabdoviridae family and the Lyssavirus genera. Rabies can be transmitted to humans through infected bites, scratches, and contact with mucosa [8, 9, 10].

The first symptoms of rabies are non-specific and appear approximately 10 days after infection. These symptoms may include fever, headache, discomfort, nausea, vomiting, etc. Near the infection site, the symptoms described are pain, pruritus, and paresthesias. Once the disease is advanced, the neurological manifestations shown are behavioral and sensory changes as well as motor deficiency. Some examples are insomnia, confusion, atypical behavior, sensitivity to stimuli such as light, air, or others; hypersalivation, and seizures [11].

Rabies can manifest in two ways: encephalic (furious) or paralytic. In furious rabies predominates the most aggressive and notorious symptoms (hydrophobia, hypersensitivity, and hyperactivity), while paralytic rabies presents with weakness in the bitten limb until reaching generalized paralysis. Finally, most rabies cases end in the death of the patient within 2 weeks [11, 12].

Rabies is related to vampirism through its symptoms since a lot of them resemble classic vampire characteristics. Insomnia, photosensitivity, hydrophobia, hypersensitivity, and spasms of facial muscles; can be related to mythical nocturnal activity, fear of sunlight and holy water, aversion to garlic, and an appearance of clenched teeth and receding lips like an animal. In addition, the vampire myth mentions the interaction between humans and animals, which can evoke a zoonosis. Therefore, rabies is a candidate disease to explain the roots of the myth, since its transmission by bite can be human-human or by animals that transmit it (dogs, bats, etc.) [13].

3. The Third: Pellagra.

Pellagra is a nutritional disease caused by the deficiency of niacin (vitamin B3). This substance is crucial in about 200 biochemical reactions, especially those responsible for producing energy. Studies indicate that pellagra develops approximately 50 days after sustaining a niacin-deficient diet. In addition, this disease is clinically recognized by the “four Ds”: dermatitis, dementia, diarrhea, and death. These four symptoms have been related to the myth of the vampire, resulting in another possible origin of vampire folklore [14, 15].

Classic vampires are characterized by staying away from sunlight to avoid burning to death. For patients with pellagra, it is also advisable to stay away from sunlight, due to a hypersensitivity towards it. Initially, this dermatitis is manifested by redness, hyperkeratosis, and scaling. Subsequently, inflammation and edema occur; followed by depigmentation among other symptoms [15].

Dementia is a consequence of neuronal and nervous damage due to the lack of niacin. The symptoms presented include disorders such as insomnia, anxiety, aggression, and depression. These behavioral disturbances have been linked to nocturnal raids by vampires [15].

In vampiric folklore, there is no mention of the form of excretion of these creatures. This possibly is because their diet is based on blood consumption instead of food. Therefore diarrhea as such is not part of the vampire symptoms. However, changing eating habits can be related to these mythical creatures. Refusing to eat food is common in patients with pellagra because they usually present lesions in the mucous membrane throughout the digestive system [15].

In the myths, it is mentioned that vampires usually return from the dead to exact revenge or finish pending matters with relatives and acquaintances. The development of pellagra is indicative of nutritional deficiency, which historically was a community problem rather than an individual one. Therefore, it was common that after one death from pellagra occurred, more would occur later. This was related to the return to life of a vampire seeking revenge [15].

4. The Fourth: Tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis is a bacterial disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. This microorganism spreads through the air when an infected person coughs, sneezes, speaks, or sings. Once the bacteria is inside the body, the infected person can develop tuberculosis disease or a latent form [16].

Latent tuberculosis occurs when the germs inside the body are not active. In this case, symptoms do not develop, and spreading the disease is impossible. However, these people are susceptible to developing tuberculosis in the future [16]. On the other hand, if the germs are active it will develop tuberculosis disease. This illness can affect any part of the body but it usually develops in the lungs. In addition, pulmonary tuberculosis is the only infectious one [16, 17]. Symptoms that may occur include weakness, fever, weight loss, and, in the case of a pulmonary infection, chest pain and coughing up blood [16].

The symptoms presented in a case of tuberculosis were what led this disease to be related to the myth of the vampire. In addition, this disease had an important presence in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries, since it had one of the highest mortality rates of the time; claiming the lives of one in four people [7]. Another mention of tuberculosis, concerning vampire folklore, is what happened in New England at the same time.

Like certain parts of Europe, New England was the scene of a tuberculosis epidemic. Many families, seeing their loved ones die and trying to find an explanation for what happened, ended up taking a solution heavily influenced by vampire myths. This led them to dig up bodies to look for signs of supernatural activity, especially fresh blood, and, in case of suspicion and to stop the spread of the disease, the heart or other organs were removed from the body and burned [18].

5. The Most-Convincing Fifth Way: Porphyria.

Porphyrins are molecules involved in the utilization, transport, and storage of oxygen. In its active form, heme, they are bound to proteins like hemoglobin; therefore their function in the human body is critical. Several enzymes regulate the porphyrin’s biosynthesis pathway, the deficiency of any of these could trigger one of the disorders where the porphyrin or its precursors accumulate. This group of disorders is called porphyrias [19].

Porphyrias are classified as hepatic and erythropoietic, depending on the porphyrin’s accumulation site. In general, hepatic porphyrias present neurological symptoms, while erythropoietic ones cause skin photosensitivity. This last symptom is the manifestation of the cell damage resulting from the excitation of porphyrins accumulated in the skin when exposed to ultraviolet rays of sunlight [20].

Among all forms of porphyria, the two most common are porphyria cutanea tarda and acute intermittent. However, the most associated with vampirism is congenital erythropoietic porphyria, also known as Günther’s disease, and its symptoms include high photosensitivity along with chronic hemolytic anemia. In addition to this, other vampire-related symptoms that can be explained with a diagnosis of porphyria are an aversion to garlic, the possession of fangs, and blood consumption. Regarding garlic, there are component substances of these plants that induce the production of heme-degrading enzymes, worsening the anemia. The supposed fangs, along with blood consumption, are explained by erythrodontia, another symptom of porphyria that occurs when porphyrins are deposited on the teeth, giving them a reddish-brown color [21].

6. The Sixth Way: Death (Not Recommended).

In addition to the misunderstanding of diseases, the lack of knowledge includes death itself. The decomposition of a body can vary depending on the environmental conditions and the type of burial, therefore a corpse can be preserved for a long time. For example, the absence of oxygen slows down the breakdown of tissue and certain levels of humidity favor the saponification of fat, this was commonly mistaken as a “live” appearance to the corpse [1]. Likewise, the gasses resulting from decomposition cause swelling in the corpse, and this also causes certain body fluids to be displaced and come out through the mouth. All this was alluding to a recent feeding by the “vampire.” Furthermore, if the body was compressed, the hiss produced by the release of the accumulated gasses could have been confused with a groan [3].

CONCLUSION

To conclude, vampires, over the years, have become an important part of literature, horror films, and other media. However, the origin of these creatures is far from the entertainment purpose that we give them today.

The figure of the vampire was created as a way to explain events such as death and illness during a time with limited knowledge of these matters. It has recently been postulated that some of the diseases that in their time may have been misdiagnosed as a form of “vampirism” were plague, rabies, tuberculosis, and porphyrias. The main reasons why these conditions have been linked to the origin of the myth are skin sensitivity to light and its relationship with blood.

Finally, it is impressive how much perception and the world as such can change after the advancement of science and medicine. For example, all the diseases mentioned above have treatment, and, of course, the myth of the vampire is now just that, a myth.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks all the writers and filmmakers for bringing great horror stories, especially vampire ones, which inspired this research. A sincere thank you to doctors and scientists dedicated to research. Thanks to them we have access to better treatments and a better quality of life. Finally, thanks to you reader for coming this far ♥

LITERATURE CITED

- Tiziani, M. (2009). Vampires and vampirism: pathological roots of a myth. Antrocom: Online Journal of Anthropology. 5.

- Lohnes, K. (2023). Dracula. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Dracula-novel

- Bundasen, L. (1998) The Natural History of Vampires. Volume 6 – 1998. Paper 2. The Natural History of Vampires (core.ac.uk)

- World Health Organization: WHO. (2022). Plague. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/plague

- CFSPH. (2012). Plague. The Center for Food Security & Public Health. https://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/plague.pdf

- CDC. (2018). Facts about Plague. https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/plague/factsheet.asp#:~:text=Septicemic%20plague% 20occurs%20when%20plague,however%2C%20buboes%20do%20not%20develop.

- Bartholdy, B. (2015). Bloodsucking Diseases: Applying Vampire Superstition to Paleopathology. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315714041_Bloodsucking_Diseases_Applyin g_Vampire_Superstition_to_Paleopathology

- World Health Organization: WHO. (2023). Rabies. www.who.int. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rabies

- CDC. (2020). What is Rabies? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/about.html

- Soler, S., Jiménez, N., Nariño, D., & Rosselli, D. (2020). Rabies encephalitis and extra-neural manifestations in a patient bitten by a domestic cat. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de Sao Paulo, 62, e1. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-9946202062001

- CFSPH. (2021). Rabies and Rabies-Related Lyssaviruses. The Center for Food Security & Public Health. https://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/rabies.pdf

- Velasco, V., Arellano M., Maria P., & Salazar, J. (2004). Rabia humana: A propósito de un caso. Revista de la Sociedad Boliviana de Pediatría, 43(2), 89-94. Recuperado en 26 de agosto de 2023, de http://www.scielo.org.bo/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1024-06752004000200008&lng=es&tlng=es.

- Gomez, J. (1998). Rabies: A possible explanation for the vampire legend. Neurology, 51(3), 856–859. doi:10.1212/wnl.51.3.856

- Kaliaperumal, K. & Thappa, D. (2002). Pellagra and Skin. International Journal of Dermatology, 41, 476–481. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Dm-Thappa/publication/11180692_Pellagra_and_skin/links/607b922d2fb9097c0cf0a852/P ellagra-and-skin.pdf

- Hampl, J. S., & Hampl, W. S. (1997). Pellagra and the Origin of a Myth: Evidence from European Literature and Folklore. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 90(11), 636–639. https://doi.org/10.1177/014107689709001114

- CDC. (2011). Tuberculosis: General Information Fact Sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/general/tb.htm#:~:text=What%20is%2 0TB%3F,they%20do%20not%20get%20treatment.

- Ait-Khaled, N., & Enarson, D. (2005). Tuberculosis: A manual for medical students. World Health Organization Geneva. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43160/WHO_CDS_TB_99.272_eng.pdf

- Bell, M. (2006). Vampires and Death in New England, 1784 to 1892. Anthropology and Humanism. https://www.yorku.ca/kdenning/+++2150%202007-8/BellVampiresandDeath.pdf

- James, M., & Hift, R. (2000). Porphyrias. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 85, 143–153. https://watermark.silverchair.com/850143.pdf?token=AQECAHi208BE49Ooan9kkhW_Ercy7Dm3ZL_9Cf3qfKAc485ysgAAA00wggNJBgkq hkiG9w0BBwagggM6MIIDNgIBADCCAy8GCSqGSIb3DQEHATAeBglghkgBZQMEAS4wEQQM ngcd-OdMvHCzVPSeAgEQgIIDAFAbAC3ooqYP8ReeFEMddolf4Cc8cyoD_KckDZM16w5RpN ZJCPsWWAFM7IgnQLwBmE66T7i8RQ21UKT1k9fs1VsayupNgA1JXAO3WmW4lbJxyYG3UvCb EQkvahRs-AYc9AwuMKsm8X_91GMl_33S7WrZerXBvbc-t-CmHrJwx09vbqrJvkojLw8y4n8 xgMOSh8MYBkxWUFQxVMSMGj_0ZTxbM-kWMpepBa7uCd3OOes-7GGGPlkOguXGESGS2 HTJjXvvxFTTed_EqqzSp8be8ZActYj_KX8vJUsggEERa6xkQQCZMwT8UGLmqlUEXhbsSR-NMlqdGmLoROuncCR7kq0BGFTg5EDZ6MiAgWtqfbVNSJmSP3mctBeVKoXVuqlQAjnS7R9G 7BuEnM44Y-GnrCPTqOYpEpAssuVHdJRob3_xJhwsmZ16s0_nRc5cwAZyxdyhB8z8y02yA _5I9dE5XA0c_UdV518wvLQxXWsj5rNTMoZpAJcP38v8z26A5b-mPykmhrQaRpm36J4aI RXhy17NlwKnxoeNnpLc1RL34eJFLi5dxPvg9eCBLAQsJn4nWX1Jxb3Jai9ILyRqRRX1VSBFQ5fO eozlKVIOvuxTjJTHCXz3fZamdyweYVyQBFrqmnOJDHmAVqoZVwDvz2zQyk6wtqnaP3pxcv5 JQbEClTgCRos2QRdEKHwgGXztX3Bd047fBPsdLRLdG4T2CMnYw8r287PgD6t_QE4fr2GuIB1 8uuuCk7dmAaXXKp4BoYelzwcSNTmbu_p1Lreic4fQuGyDrdrpwKXP7h44Hh5QDQijglbPA2U 6hlhN5Fx7ugF91xC0BYUEmMACgnRDbcLz9bqAdXKdkmLMGZL1vV06847Uk7rILZX-2CESV ZfUxBInbg1FUX0fpA2-xtym-wECsPyWLJztBoaPbRgvewkDHRSjN_Kk7ovlOh8OAtFnMum zJ-cSfiUddCaI_O-ksfBpjpwqNtiR6Altuifx03szVxhjensfy2fcz_VNlZiej0_mfg

- Medina, E., Carbajal, B., Ponce, C., & Valladares, E. (2000). Las Porfirias. Revista Médica Hondureña, 68, 1, 16–24. https://revistamedicahondurena.hn/assets/Uploads/Vol68-1-2000-6.pdf

- Maas, R. & Voets, P. (2014) The vampire in medical perspective: myth or malady?, QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 107, 11, 945–946. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcu159